Summary

Excellent production on the London Globe stage, with Hamlet an inconsequential Prince bordering on the cowardly, slowly rising (and falling) to violent revenge. Brilliantly manic performance of the Dane, enhanced within the Renaissance-style staging, complete with boisterous groundlings.

Design

Directed by Mark Rylance. Costumes by Jenny Tiramani. Fights by Rodney Cottier.

Cast

Tim Preece (Ghost/Player King), Tim Woodward (Claudius), Joanna McCallum (Gertrude), Mark Rylance (Hamlet), James Hayes (Polonius), Mark Lockyer (Laertes), Penny Layden (Ophelia), Geoffrey Beevers (Horatio), David Phelan (Rosencrantz), Harry Gostelow (Guildenstern).

Analysis

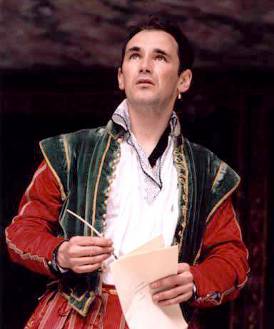

Mark Rylance and The White Company present Hamlet at Shakespeare's Globe much the same way the Lord Chamberlain's Men would have four hundred years ago - outdoors without lighting, using minimal props and scenery, and with steadfast reliance on the text. The historic setting on London's Bankside and a traditional directorial approach provide an anchor for Rylance's fresh - sometimes funny, sometimes furious, sometimes frightening - take on the title character.

Rylance portrays Hamlet as an ineffectual gentleman who decides to hide his horror, indecision, and cowardice behind a mask of manic humor. The antic disposition also conceals drastic change as Hamlet endures a series of betrayals while his world crumbles around him. Rylance's frail Hamlet seems to consider the Ghost his destiny and personal scourge as he is dragged, with kicks and screams, from being a supplicating courtier to become a vengeful Prince.

Rylance illuminates the reason for Hamlet's failure to ascend the throne of Denmark: his lack of commanding character. King Claudius masters 1.2, barking orders and directing attendants, while Rylance's black-clad Prince stands alone nearly offstage, his back to the audience, his head capped and bowed. The crowned Claudius begins passing diplomatic papers to his court concerning the possible war with Fortinbras, but he becomes dismissive and flings the papers in the air - "so much for him" - and a long kiss with Gertrude in 2.2 ceases only because of the arrival of the ambassadors. When Rylance's Hamlet approaches him in 1.2, bowing then kneeling with obedience, Claudius ignores the inconsequential Prince and instead turns to address the impressive Laertes. During the next scene, Hamlet rushes onstage for an exchange with Ophelia, but Laertes enters and begins his brotherly good-byes, and Rylance silently scurries offstage with meek embarrassment. Even the Ghost cuts Hamlet off in mid-sentence during the 1.5 murder description.

The diminutive Rylance lacks the physical brawn of an avenging prince, and in 5.2 he rolls his eyes to deride his "continual practice" at fencing. Knowing he is overmatched against the robust Laertes, Hamlet must summon courage - even at the price of his soulful innocence - and he undertakes the duel and confronts his destiny. During the fight he exhibits surprising prowess, although the Queen remarks that the Prince is "fat and scant of breath." Hamlet's success against Laertes impresses everyone, including Laertes and especially Hamlet himself, and Rylance exults, dueling with graceful flourishes.

Gertrude's long hair belies her age, as if she clings to girlish youth but is betrayed by a long swath of gray. Like Hamlet, the Queen is mild and placid, swept along by Claudius and his aggressive actions. During the 3.4 bedchamber scene, she shushes Hamlet and turns away from Hamlet's words, quite unlike his reaction to the Ghost, despite his subsequent delays.

The red-clad Claudius presents a competent King angry to find enjoyment interrupted. He delights in the 3.2 mousetrap play - booing and hissing the villain - until he realizes in mid-drink that his own act of fratricide is being depicted, and he sings and dances along to Ophelia's "distracted" 4.5 song until he realizes with horror that she has lost her mind. Claudius treats Hamlet as a mere pest until 4.3, after the Prince has killed Polonius. Hamlet plays with Polonius' severed head in a bloodied sack like a cat would with a dead mouse, although the Prince soon reveals the "head" to be just a head of lettuce. When Hamlet tells the King to seek Polonius in hell and wipes the man's blood across Claudius' face, the King loses his temper, grabs the Prince by the neck, and must be restrained from murdering yet another Hamlet.

Horatio, gray-bearded, black-caped and wise, represents both confidant to Hamlet and a quietly intellectual counterpoint to the pretentious Polonius. The counselor is mere comic relief, reading his advice to Laertes from handwritten notes, stammering in wide-eyed lack of comprehension, or exclaiming with high-pitched noises, much like the impish Hamlet, although the Prince only pretends to be a fool.

The title character dominates Shakespeare's play, and Rylance certainly dominates this production. His dry and spiritless commentary on Claudius' court and the wedding of his uncle and mother contrast with his whirling Robin Williams-like mania with the appearance of the Ghost of his father. Frightened by a 1.4 cannon shot from Claudius' revels, Rylance's Hamlet barely summons the energy to explain the situation to Horatio. Once the white-faced Ghost appears - with stately slowness, walking stiffly across the wide Globe stage in full armor - Rylance ignites: he expresses outrage at the guilt of "mine uncle!" with a hyperventilating pant; he imitates the "old mole" and calls "hello" to the vanished Ghost in a childish voice; and his condemnation of Horatio's unimaginative philosophy - "there are more things in heaven and earth" - comes in a hyperactive stutter. He swoons at "the time is out of joint" and nearly collapses, so Horatio and Marcellus must clutch his arms to help him exit.

Rylance's grasp of Hamlet's depth becomes clear in the 2.2 "antic disposition" scenes. Rylance's Hamlet does not merely disguise his intentions with his demeanor, he truly seems scared witless by his approaching fate. With wild hair and dirty face, wearing a filthy white nightshirt and socks that loll from his feet, he looks foolish, but he reveals torment at his fate, protesting "except my life" three times in rising shouts. Further, he can barely confess his "bad dreams" to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, and his "deal justly with me" to them is an earnest - and disregarded - plea.

Rylance presents an entertaining and endearing Prince, changing from inconsequential boy to vengeful force. Rylance entertains with audacious visual humor, whether it be rubbing his body with grapes during the 2.2 explanation to the adders Rosencrantz and Guildenstern of the carnal relationship between his uncle-father and aunt-mother, his feigned stabbing of Polonius in 3.2 with a drum stick, or his slapping of his own head in mock apology over his misunderstanding of Ophelia's "country matters." After the mousetrap play, he celebrates, pounding a drum and dancing a jig, then stiffens with vitriol at his spying friends - "you cannot play upon me!" - before reverting to jubilance with a shrill "God bless you, sir!" to Polonius.

Rylance also endears the audience by interacting with the swarm of "groundlings" in front of him. During the 2.2 "rogue and peasant slave" soliloquy, he points to audience members and asks them direct questions - "am I a coward?" - and when his asides draw boos from the groundlings, Rylance waves his arms to incite cheers from the galleries. His sly reference to the audience as "guilty creatures sitting at a play" leads to the "catch the conscience of the King" exultation that signals the first interval.

Rylance emphasizes the betrayals Hamlet suffers from his school friends and from Ophelia. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are portrayed as disingenuous villains, toying with Hamlet then reporting their findings to Claudius. At their 2.2 meeting, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern mirror Rylance's flamboyance, but their shielding of eyes and broad gestures seem like mockery.

Rylance portrays Ophelia's 3.1 betrayal as devastating for Hamlet. Rylance begins the scene with the gift of a book and a long kiss, then passionate sorrow, gesturing to himself to accept blame for their faltering relationship. His "get thee to a nunn'ry" is a plea for her to save herself, but when Ophelia lies to him regarding the whereabouts of Polonius - "at home, my Lord" - revealing more devotion to her father than to Hamlet, he cries a bitter farewell. He then rushes off then back onstage to retrieve his book, and he nearly spits "to a nunn'ry, go," the words now an accusation as well as a dismissal.

Rylance symbolically depicts the emotional impact of vengeance upon Hamlet. Smeared and reddened with blood - first cutting his own wrist to make the watch swear their 1.5 silence, and later from Polonius' wounds - the Prince's bloody appearance recalls the scarlet clothing of Claudius. Rylance's Hamlet becomes obsessed with death itself, as evidenced by his 5.1 fascination with the skull of old Yorick. Rylance plunges into the deceased clown's burial pit to join the gravedigger, makes the skull's teeth chatter, then gazes at it in wonder as the bells toll for Ophelia's funeral march. He raises the skull to Laertes in mock-salute at "and dog will have his day," and a series of similar skulls adorn the stage for the duel between the two men.

Rylance eliminates the 4.4 martial march to Poland as well as the playful 5.2 exchange with Osric to accelerate the pace toward the climactic duel. His Hamlet insists that he does not mock Laertes, and he seems sincere, although moments later Rylance clucks like a chicken, and his second hit - "a touch, I do confess it" - is a lusty stab between Laertes' legs.

The conclusion packs satisfying punch. Gertrude's drink from the poisoned cup elicits a gasp from the audience, and she collapses where Laertes soon falls. Claudius embraces the dying Queen, and when Rylance's Hamlet confronts the King, there are shouts of "treason!" as the rugged King defends himself with a dagger. Hamlet finally dispatches his father's murderer with a brutal stab to the neck and then dies while still standing - "the rest is silence" - so Horatio must lower him to the ground for the "flights of angels" speech. Fortinbras' soldiers arrive and enwrap the avenging Hamlet's body in scarlet red cloth - completing the bloody color symbology - then carry him offstage as a cannon fires.

Rylance leads the curtain call in another striking stage image. The cast returns, solemnly marching and rhythmically pounding skull-topped staffs upon the stage. The image would be a perfect conclusion for this at times excellent production, but Rylance segues the death march into a traditional Elizabethan-style post-performance jig, with the entire cast playfully dancing, now accompanied by clownish reapers and skeletons. The festive conclusion, albeit traditional, somewhat diminishes the play's tragic impact, although Mark Rylance's insightful portrayal of Hamlet remains memorable.

Note: A version of this article was edited and published in Shakespeare Bulletin, Vol.19, No.1, Winter 2001.