Summary

Expertly realized modernization within a just-a-nightmare framework features an excellent Hamlet and Ophelia and is bolstered by a great-friend Horatio and a complexly textured Polonius. Superb imagery ranges from the mirror-image Hamlet about to take revenge to the suspended-in-air drowned Ophelia surrounded by floating roses, along with a recurring blood-red color theme in an often fascinating and always entertaining production.

Design

Directed by Richard Garner. Scenic design by Kat Conley. Compositions by Kendall Simpson. Costume design by Sydney Roberts. Lighting design by Mike Post.

Cast

Carolyn Cook (Gertrude), Allan Edwards (Polonius/Gravedigger), Dan Ford (Marcellus/Lucianus), Neal A. Ghant (Laertes), Ann Marie Gideon (Ophelia), Chris Kayser (Claudius), Mark Kincaid (Ghost/Player King/Gravedigger), Joe Knezevich (Hamlet), Tony Larkin (Francisco/Rosencrantz/Osric), Eric Mendenhall (Horatio), Tiffany Denise Mitchenor (Lady Margaret/Player Queen/Priest), Eugene H. Russell, IV (Guildenstern/Priest).

Analysis

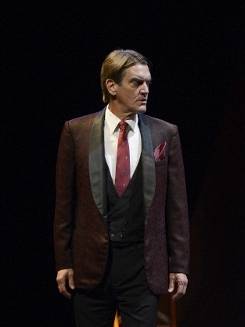

Georgia Shakespeare's production of Hamlet at Oglethorpe University is a modernized re-telling of the tale as the title character's nightmare. Director - and artistic director - Richard Garner begins with an echoing guitar power-chord and a glimpse of the 5.2 bloodbath at the end of Hamlet, Joe Knezevich's Prince dead but cradled in the arms of Horatio, Laertes and Gertrude and Claudius fallen around them. Two tall but narrow mirrors, each looking close to eight feet in height, are shifted behind Knezevich's noble-hearted Hamlet, angled to show the audience his reflection, and he jerks awake with a startled shout, Ophelia emerging from upstage right to comfort him. Knezevich's Hamlet exudes charisma, dark-haired and suave, handsome and confident, wearing a white suit that looks suitable for late-night clubbing, his emotional disarray revealed only by lack of tie, his black arm-band, and most notably, a lack of socks and shoes. He moves about the stage 1.2 in bare feet, his speech quick but stuttering in rhythm, and Ann Marie Gideon's enrapt Ophelia tries to go to him, but is prevented by Laertes, who pulls her away offstage. Hamlet seems to lose his confidence during his confessional soliloquy to the audience, sinking to his knees before the mirrors to bemoan the passing of his father.

Knezevich's Hamlet, despite his debonair charm, reveals honest emotion in 1.4: gestured upstage by the Ghost of his father, he pursues in eerie blue light, and when he finally catches up 1.5, he is overwhelmed, covering his mouth with both hands before he crouches to embrace his father. His vigor seems renewed by the bloody task at hand, as he nears rage at Claudius - "smile and smile and be a villain" - and when he makes Horatio and the guard swear silence, offstage lights pulse, an amplified voice intones, "swear!" and Knezevich whirls like a dervish. Marcellus and Horatio cross themselves as if for protection and Hamlet puts their fingers to their own lips: "sh."

Garner and his designers subtly infuse the stage and costumes with cinematic splashes of crimson - a red rose here, a scarlet scarf there - much akin to the Shyamalan film, "The Sixth Sense," here the sanguine color presaging the coming bloodshed. Claudius and Gertrude celebrate 1.2 with courtly decorum, red robes draped over their modern clothing, he long-haired but looking a bit older than his new spouse, she cougar-style sexy in kicky high-heeled boots, bared shoulders, and black tights. When Chris Kayser's lean Claudius, with a facial expression somewhere between hatefully sanctimonious and reverently pious, puts a red scarf around Hamlet's neck, Knezevich flinches and moves backward. Later in 2.2, after the revelations from the Ghost, the Prince rises to confront the King but Gertrude restrains him by the shoulder, and he only glares as the royal couple exit, hand in hand.

Allan Edwards' deeply nuanced Polonius sports a crimson bow-tie 1.2, orchestrating the ceremony for Claudius and Gertrude, handing the King a silver goblet of wine as Laertes approaches amid the noise of fireworks, bold in his blazing red shirt. Moments later in 1.3, Garner cuts to Laertes in a hoodie, packing for school while he warns Ophelia against Hamlet: "his will is not his own." Gideon's ethereal Ophelia dances around him in a scarlet-flowered white dress, carefully childish enough to seem not so much immature as a little off, and she straightens her brother's scarf, laying a palm on his forehead as if exorcising demons. Notably, when she discovers a bottle of liquor in Laertes' luggage, she is careful not to let their father see, choosing loyalty to her brother over obedience to her father. She also gives a girlish pinky-swear to Laertes and then a big waving send-off.

Polonius seems realistically paternal, at times concerned and controlling, at others gentle and sympathetic. He reads his daughter's love letter from Hamlet aloud 2.2 while she cringes with embarrassment, and he approaches the Prince just moments later, following Garner's earlier placement of the "to be or not to be" soliloquy. The speech is memorably searing, Knezevich's Hamlet wielding a dagger with one hand while flipping the pages of a book with another, symbolically torn between his thoughts and his emotions. After Hamlet nearly bursts into tears - "except...my life" - Edwards' departing Polonius pauses and turns to place a warmly empathetic hand on Hamlet's shoulder.

During a superbly played 3.1, Edwards' Polonius leads an emotional fragile Ophelia onstage, tugging at her elbow, and she carries an appropriately dark red box of love tokens and mementos from Hamlet. Gideon's Ophelia weakly tries to return the red box to Hamlet, but Knezevich refuses and backs away, his words alternating between hurtful - "I did love you, once" - and somehow protective, if essentially dismissive: "get thee to a nunnery." After she glances to the hiding place of her father and the King, Hamlet realizes he is not only being doubted, but actively deceived - "where is your father?" - and after a long and injured moment of silence, the scene becomes intense. Knezevich's wounded-animal Hamlet teeters on the verge of violence, and he tears up his love letters and tosses the little red box at Ophelia. He manhandles her to the mirrors and her reflection, then again downstage, and he whips down her necklace before finally advising her in a sad near-whisper, "to a nunnery, go." Gideon's Ophelia sags to her knees in tears and crawls to begin collecting the torn fragments of the love letters as Edwards' Polonius enters and moves past center stage. In a moving moment, Polonius drops to his knees and silently helps his daughter collect the fragments of her treasured love notes, and when they finish, he embraces her as if holding her together.

Garner gives attention to a plethora of details in this astute production. Even a role as small as Horatio is given careful significance with his first appearance 1.1 accompanying the frightened Watch. Eric Mendenhall's Horatio represents Hamlet's intellectual side, a tall and lean life-long college student with long curly hair and wire-rim spectacles. The trench-coated Watch seem terrified - "who's there?" - piercing the darkness with flashlights as Horatio - or, "a piece of him" - arrives with the look and body language of a computer programmer. He makes like a ghost, using the flashlight under his chin like a teenager's scary trick, but is suitably humbled and disturbed by the Ghost, especially during his 1.2 revelation to Knezevich's Hamlet. At 3.1 Hamlet gestures to his heart when describing his friendship for Horatio, and during the subsequent mousetrap performance, Claudius rises and wobbles, grasping at a lantern, and Mendenhall's Horatio stands open-mouthed in pointing accusation as Knezevich's Hamlet dances a victorious jig. In a memorable stage picture, Horatio reads Hamlet's 4.6 letter downstage right, and Garner brings lights up on Hamlet upstage in the glow from a single candle, seated at a desk, quill in hand, writing to Horatio as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern sleep behind him. Knezevich gradually begins reciting the letter himself, telling the story of pirates and escape and hanging, finishing with a dramatic flair as he brings a blackout by blowing out his candle. Further, Mendenhall's Horatio leaps between Hamlet and Laertes during the 5.1 scuffle in the graveyard, embraces Hamlet fondly before the duel 5.2, helps the wounded Prince to center stage after the fight, then holds him for his final words: "the rest is silence." Mendenhall's voice breaks with emotion, his friendship believably played as he groans, "now cracks a noble heart."

In contrast to Horatio are "the adders fang'd," Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, one tall and one short, arriving 2.2 as Hamlet's low-brow frat drinking buddies, giving a high five down low, a chest bump, even a comic push to the chest while one of them kneels behind Hamlet. They seem to represent Hamlet's emotional side and do what they are told to do. When Knezevich's Hamlet determines their complicity if not their lack of honesty - "you were sent for!" - he sits center stage, betrayals mounting, and pulls out a flask. They try to join him, but he sends them off to greet the Players. In 3.1, Garner shows the two following behind Claudius and Gertrude like guard dogs, and when one places a menacing hand on Hamlet's shoulder, Knezevich shoves him away and puts an accusatory finger in both their faces. In 4.2 Hamlet flings theatre chairs in their way as they pursue him, at one point keeping them at bay by holding a chair legs-out like a lion tamer.

Knezevich's Hamlet seems to trade places with Polonius during the 2.2 and 3.1 interaction with the players, greeting them with happy shouts, then with detailed over-direction - "do not saw the air" - while Edwards' Polonius just sits bored, his cheek in his hand. Knezevich is masterful, whirling from anger - "who shall 'scape whipping?" - to utter dejection - "I am alone" - then to the eloquent self questioning of the "what a rogue and peasant slave am I" soliloquy. He cries out for vengeance and drops dramatically to his knees, only to wince and give the audience a sheepish "ow" that precedes "what an ass am I?" After the Mousetrap play, he becomes resolved: "now 'is the very witching time of night." With Kayser's rattled Claudius alone and kneeling in attempted prayer - "my offense is rank" - upon a bright red pillow, Knezevich's Hamlet approaches from behind and between the two mirrors. In a startling image, he steps between the mirrors, his reflections now on either side of him, so he is cut into three - Hamlet fractured - as he raises his knife amid a power guitar chord and a sudden blackout that signals intermission.

Garner resumes with a gentler piano chord, and Knezevich's Hamlet backs away - "he took my father grossly" - from Claudius, who rises to his feet. Kayser's Claudius seems conflicted, showing more than a few signs of humanity: he kneels 4.1 beside Gertrude to comfort her after the confrontation with Hamlet; he seems saddened by Ophelia's 4.5 madness, and she embraces him with genuine trust and warmth; and in 5.2 he moves past Hamlet to the poisoned Gertrude, beginning to sob at her passing. Less conflicted is Gertrude, who appears to be more than a trophy wife but not quite a power-hungry schemer. She seems truly insulted by Hamlet's 3.4 words - "your husband's brother's wife" - as well as by his advice - "assume a virtue if you have it not" - and is lacking in complicity, shocked at the mention of murder and not even suspecting the wine has been poisoned during 5.2.

Gideon's lovely Ophelia, however, buckles under pressure, arriving 4.5 with her hair down and her legs bare, clad only in the bloody white shirt Polonius was wearing when he was stabbed. She makes zombie-like herky-jerky movements, clutching her red box of shredded love letters. Lit in the same blue light as Hamlet was during the Ghost scenes, Gideon's Ophelia uses red roses as a pillow to lie onstage, and she wraps the roses in a red scarf. The performance is searing, Gideon singing like a lost child to her brother - "pray love, remember" - from depths of despair that are beyond Claudius or Gertrude and being resisted mightily by Knezevich's Hamlet. Garner cuts to 5.1 and the imagery is again breathtaking, a heartbreakingly lonely Ophelia elevated above far upstage as if she is floating, drowned in the river, rose petals swaying around her. She seems ghostly pale, but finally at peace, and the raw humor of the Gravediggers - pointedly, the same actors who portrayed the fathers of Hamlet and Ophelia - seems earthy but grating. One uses a long ribbon of scarlet-red cloth to demonstrate to Hamlet and Horatio the mechanics of drowning, and he flips to Hamlet the skull of Yorick from the end of a shovel, later making the bones "laugh" by moving the jaws as if playing with a parlor trick. But once Knezevich's Prince makes his realization - "what, the fair Ophelia?" - among tolling bells and a long-stemmed red rose from Gertrude, Hamlet shoves the gravediggers aside and grapples with Laertes.

The concluding 5.2 duel ties the interlocking themes, Hamlet first mocking the foppish Osric with a big bow, then donning goggles and gloves to duel Laertes. He clasps both of Laertes' hands in his with a humble apology, but is refused, and moments later Gertrude unknowingly drinks from the envenomed cup, and she gasps and blinks, gives a tremble, and wipes her face. The fighting becomes furiously paced as first Hamlet then Laertes is mortally wounded, and the King tries to defend himself but Knezevich's Hamlet stabs him, wraps the red scarf around his neck to strangle him, then forces upon him a cup of poison. The torturous nightmare begins to end with Hamlet's final words - Fortinbras is entirely cut - as Ophelia emerges from stage right, the production concluding upon a dramatically satisfying - if too often done - twist of "it was all just a dream."