Summary

Shakespeare's slight romantic comedy is given a delightful outdoor production, modernized into a colorful buddy-movie a la The Hangover. Well conceived and directed - and hugely entertaining - with a rock music video and a cream pie fight in the same scene. Consistently well-performed supporting characters and comedic flourishes not only entertain but enliven the hormonal young-love situations.

Design

Directed by Shana Cooper. Scenic design by Christopher Acebo. Costume design by Christal Weatherly. Lighting design by Marcus Doshi. Compositions and sound design by Paul James Prendergast. Choreography by Jessica Wallenfels.

Cast

Mark Bedard (Ferdinand), Gregory Linington (Berowne), Ramiz Monsef (Longaville), John Tufts (Dumaine), Kate Hurster (Princess), Stephanie Beatriz (Rosaline), Tiffany Rachelle Stewart (Maria), Christine Albright (Katherine), Robin Goodrin Nordii (Boyet), Jack Willis (Don Armado), Emily Sophia Knapp (Moth), Gina Daniels (Jacquenetta), Charles Robinson (Nathaniel), Michael Winters (Holofernes), Brad Whitmore (Dull), Jonathan Haugen (Costard).

Analysis

Shana Cooper's outdoor production of Love's Labour's Lost is played upon stage grass and patches of purple flowers, with a flagless flag pole and a wooden ladder leading up to a gallery, and a tall slatted fence upstage. Ferdinand begins the production with a telling comic prologue, emerging in full rugby gear from behind the fence, clutching a football as he calls signals, runs in slow motion, mimics crowd noises, and does a victory dance. He is joined by his rugby-style maturity-challenged buddies like the bachelor party-goers in The Hangover, and they reluctantly part with worldly belongings into a center stage trashcan: Dumaine surrenders a box of doughnuts; Berowne parts with a box of cigars and a teddy bear; and Longaville unloads an armful of porn magazines. The buddies all pause a moment to appreciate a multipage centerfold one last time before bringing out an inflated blonde sex doll, giving "her" an odd "zero" salute, and sinking her headfirst into the trashcan. They then don school sport coats and fez-like hats, setting a decidedly lighthearted tone for this inventive frat-boy rom-com combo.

The appropriately named Constable Dull moves to center stage to deliver pre-curtain admonitions against "cellulite devices" and "flesh photography," Cooper's audience already delighted although the play has not yet actually begun. Then Ferdinand and his compatriots, all wearing cleats and kneepads, their surnames stenciled on the backs of their rugby jerseys, discuss their 1.1 oaths of self-denial. A sign with a red slash through the silhouette of a woman hangs from the fence behind them. Berowne pleads in vain - "I swore in jest!" - and they share high fives and tackle Berowne when he finally signs, Longaville taking special care to sit on his friend's face. Their preppie schoolyard antics are contrasted with the tattooed letter-delivering Costard, who evokes a high school burnout in his T-shirt and jeans with boots, his strut and pompadour something of both The Fonz and a James Dean-style rebel.

The supporting characters of 1.2 are even sillier, the Constable returning in his yellow button-down shirt with blue pockets, a tie, and a police bonnet, twirling his billy club. Don Armado is a bald and portly cross between a magician and a Spanish conquistador, waving a wand and lisping thickly as his diminutive page Moth flirts with and fist bumps Costard. Armado stutter-rumbles "I am in love" as Moth massages his back and places his helmet atop his head, and Jacquenetta proves a wordless wench in cowboy boots and a country dress, licking a lollipop. Armado's exultations of love complete the scene as glittering blue and green confetti drifts down upon him.

The rom-com returns with a colorful splash as the Princess and her attendants arrive 2.1, smiling and giggling as they pose for snapshots by the martini-toting dorm-mom Lady Boyet. The ladies are color-coded to match the attire of their romantic counterparts - the Princess in yellow, Rosaline in blue, Katherine in pink, Maria in green - and they haul luggage cases and hat boxes, assisted by an unsteady Boyet. The attendants check the lipstick of the Princess, remove her stole, and put on her tiara as Ferdinand and the boys arrive to a trumpet fanfare. Flirting begins immediately - Stephanie Beatriz's Rosaline, barefoot and with blue flowers in her hair, bends way over in front of an awed Berowne - but the boys are nervous, tongue-tied and clearly overmatched, as evidenced by Ferdinand stuttering over the word "breast." He is scolded by his friends - "ah! ah! ah!" - when he nearly takes the Princess by the hand, and they gesture to the "no women" sign as they stomp off upstage. The behavior is adolescent, but the presentation and delivery are fresh and funny, and the girls make racy jokes by thrusting a flashlight into a rolled up sleeping bag, accept a bucketful of toilet paper from Ferdinand (who closes the fence gate on his own head), then adolescently toilet-paper Boyet in a running circle of girlish laughter.

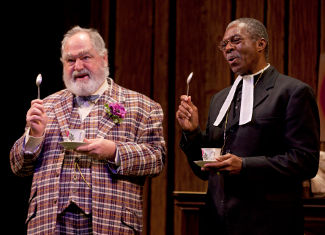

Cooper glides through the mistaken letter sequence - 3.1 and 4.1 - with Costard arriving like Mercury in a shimmering blue and green toga, Berowne soliloquizing shirtless with a gym towel and boxing gloves, then the ladies (in orange vests and hunting hats) wielding bow and arrow. After the girls scream shrilly then ooh and aah at the supposed love letter from Berowne, an armchair and ottoman are wheeled onstage for 4.2, followed by a fireplace with books on the mantle. Nathaniel and Holofernes take center stage, nicely underplayed egghead scholars, spouting eloquent gibberish as if tea time at Masterpiece Theater. The Constable sits nearby with a sandwich, sipping with a straw from a juice box, his expression one of perpetual confusion.

The 4.3 exposure of the love struck frat boys is the centerpiece of Cooper's production, a charmingly played sequence that builds with each arrival and every confession. Berowne begins, his sad sonnet on blue paper, and he hides up in the balcony as Longaville arrives in a green camo hunter's outfit, his love letter covering both sides of a construction-paper heart. Longaville pours water from a canteen over his head as confetti falls again, and he in turn hides - sprawling offstage left in a mad scramble - as Dumaine enters in fishing gear (including hip waders) with his own love letter, written upon a roll of toilet paper. He too conceals himself as Ferdinand arrives with a bottle of Makers Mark bourbon, dejectedly smoking a cigarette. Cooper then pushes the envelope, stunning the audience as Ferdinand hits the on button of his boom box and spins upstage. The lights suddenly begin to pulsate as he sings in an impromptu rock music video, wielding the bourbon bottle as his microphone. When Berowne, Dumaine, and Longaville join in as backup singers - complete with choreographed moves from arm twirls to flailing spins to hip thrusts - Ferdinand carnally massages himself with pages of love letters for a big finish, and the audience wildly applauds. But Cooper has not yet finished with her thunderbolts, and Berowne slides down the flagpole like a fireman to confront his friends, then rushes into the audience to attempt to conceal one of his love poems to Rosaline. Accusations are flung, and soon so are cream pies, as the horseplay devolves into a full-fledged pie fight, white cream flying across and from the stage. After they all finally sit still to listen to Berowne's poetic thoughts about love, they gather in a sports huddle and cheer - "let us lose our oaths to find ourselves" - as confetti falls again to signal a rather late intermission.

It would be difficult for Cooper to maintain this pace and inventiveness during a brief second act - Shakespeare's Act 5 - but she and her cast make a game attempt. Cooper begins with another interlude as a drunken Boyet, wearing sunglasses and a floppy hat, spills her martini while Dull enters, waving his club when he hears an apparent cell phone ring from within the audience. 5.1 begins with another appearance by Holofernes and Nathaniel, this time swilling brandy from snifters as Armado speaks of meeting "in the posterior of the day" and Jacquenetta waves a home pregnancy test kit at Costard.

The second act highlight is the Princess and her ladies' 5.2 manhandling of the supposed Muscovites. They raise their own tent, leaving one lady dangling from a rope stage right, then lounge in color-coded pajamas and matching shower caps and sleeping bags like teenagers at a sleepover. They laughingly compare love "tokens" - ranging from a T-shirt with poems handwritten upon it, to a sparkling wonder bra, to a pair of long pink rubber gloves - while the perpetually tipsy Boyet uses a radar-like listening device and earpiece to scan the woods and eavesdrop on Ferdinand and the boys. When they arrive in disguise as Muscovite dancers, they all wear tight - way too tight - white stretch pants with masks, fur hats, and fake mustaches and beards. They dance badly in crimson light, their accents absurd, their silliness boundless: as Berowne later notes, "we are shame proof, my lord."

Once the ladies have suitably humbled the men, and the quartet of couples have paired off, Cooper begins the conclusion with the court presentation of the Nine Worthies. The always difficult scene is the weakest of the production, Dull in the balcony with a bucket on his head, playing percussion upon a drum and cymbal as the couples munch popcorn and hurl insults, a scene almost identical - but inferior - to that in the later A Midsummer Night's Dream. When the bad news is revealed regarding the passing of the Princess's father, the mood darkens and surprisingly, remains dark. Armado drops his accent, leading Jacquenetta away by the hand, and despite Maria's flirtations - coyly twirling Longaville's tie - and Rosaline's frustration - she flings Berowne's love letters back at him - the couples share a last dance until finally Rosaline joins Berowne. The Nine Worthies performers - horrible before, excellent now - alternate in lovely crooning at center stage. Their song is a Spring/Winter ballad, the lyrics a subtle evocation of the springtime immaturity of the young lovers, and amid falling confetti the suddenly wise Armado utters the words that sadly conclude this spirited production: "you that way, we this way."