Summary

Hollywood-style action movie set in an unconvincing modernization of Chicago. A huge budget with lighting effects and projections, but an episodic - occasionally superb, usually striking, sometimes pretentious - approach. Well played socialite Lady Macbeth and career-soldier Macbeth. Some effective drama and horror, but characterization is subdued within elaborate imagery and expensive production values.

Design

Directed by Barbara Gaines. Designed by Mark Bailey. Lights by Philip S. Rosenberg. Sound and compositions by Lindsay Jones. Projections by Mike Tutaj. Special effects by James Savage. Fights by Robin McFarquhar.

Cast

Ben Carlson (Macbeth), Kate Buddeke (Witch), Angela Ingersoll (Witch), Mike Nussbaum (Witch/Porter), David Lively (Duncan), Phillip James Brannon (Malcolm), William Dick (Lenox), James Newcomb (Ross), Danforth Comins (Banquo), Karen Aldridge (Lady Macbeth), Evan Buliung (Macduff), Erik Hellman (Donalbain), Rengin Altay (Lady Macduff).

Analysis

A modern press conference begins this production of Macbeth, with a crush of reporters and crew wielding microphones and cameras while jockeying for position around a presidential Duncan. The chopping sound of helicopters passing overhead can be heard as the news reporters shout questions regarding the "war" against the Thane of Cawdor. One reporter - obviously a witch by her appearance - shoots upstage-projected video close-ups of Duncan with a hand-held video camera. The other two witches - one male, one female, both pale and dark-eyed, wearing long black coats - clamor among the throng of reporters. The questions arise early: are these evil spirits of ambition a product of the modern political environment, or are they the creators of the environment, akin to the media creating the news? Ben Carlson's Macbeth, in military beret and sidearm, witnesses the press conference from the periphery, not yet mired within the political milieu but certainly vulnerable.

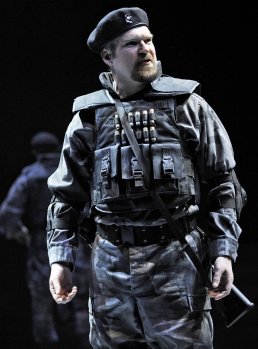

Carlson's Macbeth first appears within Barbara Gaines' Hollywood-style action movie version of Macbeth in a prelude with Banquo. The stage swarms with modern combat soldiers in camouflage, body armor, and helmets, aiming automatic rifles. The red dot of laser-sighting appears on them and they crumple as offstage gunfire erupts; Macbeth and Banquo then rush onstage and with a decided lack of valor, kill the moaning and wounded survivors with bursts of rifle fire. Gaines counterpoints the cold-blooded pragmatism of their actions - bloody and ruthless - by juxtaposing them with gruesome images of the witches on the heath. Amid swirling fog lit with bright spot lights from the side as well as ghastly yellow spots from above, the ugly and animalistic witches - albeit obviously human - gnaw at pig entrails and swig from liquor bottles, with the third using her camera to again capture video images, this time of Macbeth and Banquo. The ambition of Carlson's Macbeth - lean and soldierly with his assault rifle, bullet-proof vest as "armor," and combat knife sheathed to his ankle - is apparent in his grimly determined expression projected in extreme close-ups on the upstage screen.

Carlson's introspective and haunted Macbeth, while appropriately strident vocally and aggressive physically, is dwarfed by the production's large-budgeted special effects. The updating to contemporary Chicago - Duncan makes his announcement regarding Malcolm to reporters and photographers while standing in a business suit and tie like the mayor of the city upon a makeshift platform behind a podium - lends little but modernity to the already universal themes of the play. Carlson's Macbeth leads the applause for Malcolm and Duncan, but a witch wisely captures his expression of disappointment and rising anger, flashing it across the upstage screen. When Carlson kneels to summon the courage for the murder of the King, he is caught within a bright circle of light and speaks to a ghostly knife ("is this a dagger I see before me?") that only he can see. He then brandishes his own combat knife, but inadvertently cuts himself on the blade, with the extremely subtle allusion being that the witches and ghostly images are not providing Macbeth with weapons but with the idea to arm himself with his own weapons. Carlson's ambitious Macbeth is therefore not so much violated as he is seduced.

The portrayal of Lady Macbeth seems much more suited to the contemporary framework. Karen Aldridge's striking Lady, an African-American with long straight black hair, wears a short white negligee nightgown during her first scene, lounging in her penthouse apartment before an upstage backdrop of an evening skyline of Chicago. She owns a swanky art deco home, replete with twin black leather couches and an array of candles burning in tall glass holders, and she makes the costume changes of a popular-music diva, appearing in a series of glitzy creations: a glittering silver dress for Duncan's arrival at Dunsinane; a flowing crimson gown for her husband's coronation; a spunky pink mini-dress for the ensuing celebration; and an elaborate golden gown for the banquet haunted by Banquo. Much moreso than Carlson's mercenary Macbeth, Aldridge's slinky Lady is a product of the times, defining herself by her home, her wardrobe, and her belongings, ambitious and narcissistic, using herself as a tool to acquire even more. To inspire the uncertain Macbeth toward regicide, she grasps his arms and kisses him, leaving him longing for her as she moves away and slips into her onstage bathtub, topless and seductive, all but naked and using sex to get her way.

Gaines provides a slew of brief and evocative images - Duncan dances with Macduff's little girl, dipping her to squeals of delight along with applause from the party guests; the Lady closes the curtains to Duncan's bedroom, and moments later an owl shrieks fearfully; a gigantic overhead airport terminal board details arrivals and departures as Malcolm anxiously waits, with flights suddenly becoming "cancelled" in ominous red block letters - but there is little continuity between scenes, and the production seems to lurch from big splashy scene to big splashy scene. The porter (one of the witches in the more benign configuration of a terry cloth robe and slippers) shuffles at audience level to answer the knocking. He banters with the audience - "here's a banker, here's a lawyer, here's a lusty wench" - and earns a laugh upon encountering a critic: "You're already in hell."

The witches reveal to Macbeth the lineage of kings within a sleazy strip club. As half a dozen stripper-attired women gyrate to the grind of heavy-metal guitars, amid flashing red lights and lewd projections of their shadows upstage, the witches drink whiskey and pull body parts from passed out patrons as ingredients for their cauldron brew. They sing the curses, shouting "show" to stun and taunt the enraged Macbeth. Banquo himself is shown as a crowned King, turning on a slowly spinning dais as brilliant flashes of light reflect and shoot from a small upstage wall of mirrored tiles. Less effective (but even more flashy) is the attack upon the Macduff household, with the children singing karaoke into a microphone and playing pretend guitars. Their song, ironically, is the 1980s Blondie hit "One Way or Another" - "I'm gonna getcha getcha getcha" - and the killers, wearing leather jackets and ski masks (one slashes his way through the wall paper with a switchblade), stab the older child and snap his neck to a sudden, silent blackout. The over-the-top melodrama of the sequence borders on parody, like something from a campy Hollywood slasher movie spoof (and not a good one) rather than relying on the vulnerability and raw-and-gritty fear called for by the scene.

Gaines wisely subdues the banquet scene and the appearance of Banquo's ghost, eschewing splashy theatrics in favor of clear characterization of Macbeth and his Lady. Amid martial drumming, the image of Banquo appears, bloody-faced and angry, in a close-up projection over Lady Macbeth's seat at the table, as Carlson's Macbeth attempts to offer a celebratory toast with his flute of champagne. Carlson shows genuine alarm, doubling over not in fear but in horror at himself, and Aldridge's statuesque Lady seems to show more annoyance that her cocktail party is ruined than concern for her husband's political career (or trepidation for his mental health). When Banquo appears in person, still bloody across his face and chest, he staggers after Carlson's Macbeth and pursues him bodily around the table, and the panic apparent in Carlson and the amazement of his guests is clearly depicted. Aldridge's Lady concludes the scene with a dramatic flash of peeved temper, swiping all the table settings from the banquet table to the floor. The production's finest moment is also Aldridge's, when she appears in a flowing white dress deep upstage, sleepwalking but stopping in her tracks with her legs wide and her arms outstretched. Her white-clothed body becomes a projection screen for bloody and violent images and she contorts with horror amid ominous music, the pain and terror brilliantly shown to be physically within the character. Aldridge's Lady finally doubles over with an agonized shout, and the scene dramatically blacks out.

Carlson's Hamlet - albeit not as fiercely intellectual as his Hamlet on the same stage in 2006 as well as at the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in 2008 - still finds some piercing personal moments deep beneath the special effects: checking discretely that his hands are clean when the body of Duncan is discovered; throwing crumpled documents at the fleeing thanes and attendants; and especially, sagging slowly upon the discovery of Lady Macbeth, twisted with her arm behind her, naked in the bloody water of her clear glass bathtub. Carlson's Macbeth delivers his gut-wrenching "tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow" speech with the same clearly-voiced tortured pain as the despondent Dane. One wishes Gaines would have found a way to afford him more moments such as these.

Gaines' conclusion - with her underplaying of the Birnam wood scenes - comes with still more stylized violence, as Macbeth's visored and helmeted riot police create an upstage wall with their shields. Macbeth executes an enemy soldier at point blank range, and his knife fight with Macduff, long and laborious with wild swings and much shouting, concludes when the two Scotsmen crash through the barrier of riot police. Macduff emerges, shoving his way through, and he lofts a bloody burlap bag that supposedly contains Macbeth's severed head. He presents the bag as a symbol of victory to the politic Malcolm, who in turn delivers the concluding passages as a presidential speech at a podium, giving a carefully posed smile to flashing cameras and canned applause. The crew of reporters and photographers mill about in front of him, including the three witches, and when Malcolm's smiling face appears in a grainy-imaged projection upstage, Gaines achieves a decided sense of déjà vu and circularity, with history repeating itself and ruthless ambition underscored as an undying human characteristic.