Summary

Makeshift production at a nearby Armory due to the temporary closure of a theatre building, this hastily remounted problem comedy is set during 1975 within an American inner city. Despite an effectively dramatic strolling musical chorus, the production emphasizes comedic elements, especially over-the-top caricatures that blunt the central conflict and the theme of injustice perpetrated by the empowered.

Design

Directed by Bill Rauch. Scenic design by Clint Ramos. Costume design by ESosa. Lighting design by David Weiner. Compositions and arrangements by Susie Garcia. Music supervision by Michael Keck. Choreography by Alonzo Lee Moore IV.

Cast

Anthony Heald (Duke of Vienna), Isabell Monk O'Connor (Escalus), Rene Millan (Angelo), Kenajuan Bentley (Lucio), Cristofer Jean (Mistress Overdone/ Abhorson), Ramiz Monsef (Pompey), Frankie J. Alvarez (Claudio), Alejandra Escalante (Juliet), Stephanie Beatriz (Isabela), Tyrone Wilson (Elbow), Brooke Parks (Mariana).

Analysis

The Oregon Shakespeare Festival remounted several productions - including Measure for Measure - at a nearby Armory when their state-of-the-art Angus Bowmer Theatre was unexpectedly closed due to an unsafe support beam. This remount suffers from minimalized lighting and sets, and especially from the loss of Shawn Sagady's projections and video design that gave the original production a more distinctive sense of locations. But the cast and crew demonstrate remarkable fortitude - the show must go on - with performers on a sparse stage, its audience seated on metal folding chairs in the Ashland Armory. The "new" Measure for Measure unfortunately plays like a staged reading or a dress rehearsal in a black box space. Star Stephanie Beatriz thanks the audience and encourages patrons to use their imagination to conjure a conference room, a whorehouse, a convent, a prison, and appropriately enough, a community center. The set at the "temporary home" is just a conference table and chairs in front of a couple of white hospital screens upstage.

The production begins with a trio of uniformed Hispanic cleaning ladies slowly working across the stage with mops and dusters and rags. They pick musical instruments from a cart - a violin, an acoustic guitar, a heavy Spanish guitarron - and move downstage to sing, a sign on an easel at stage left indicating their "Song of Work." The musicianship and singing by Las Calibri - Susie Garcia, who also composed the songs, along with Mary M. Alfaro and Vaneza M. Calderon - are exceptional and evocative of the plight of the lower class, easily the best element in this improvised production. Director Bill Rauch modernizes Shakespeare's play to a decaying American city during 1975, with the musicians a strolling Chorus. Their songs are indicated by titles on the easel: as visitors of prisoners in 2.3 they pump their fists at the end of the Song of Social Justice; they begin the second act 4.2, crouching together to sing the plaintive Song of Death Row; and they underscore the pain of Mariana in a mental hospital with their Song of Lost Love.

Rauch begins the production proper with the 1.1 abdication of the Duke, a harried executive, mustached and bespectacled, in a work shirt with suspenders and a red necktie. Anthony Heald's Duke hauls onstage two pieces of luggage and a briefcase, sitting with Escalus - a prim and almost always silent black woman - at the conference table as the house lights finally fade. Angelo, a young and handsome Hispanic with slicked back black hair, pointedly sits at the opposite end of the table.

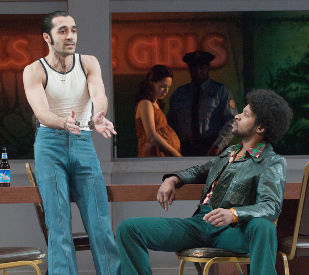

Rauch shifts from the somber sterility of the government office to the boisterous whorehouse of 1.2, as three scantily clad dancers climb atop the conference room table while seedy men tip them with dollar bills and drink liquor from flasks. The characters are retro-attired and broadly played, Mistress Overdone a cross-dressing man in a long wig and a leopard pant suit with a red sash, and Lucio a mid-'70s stereotype, an uneasy cross between Samuel L. Jackson and Huggy Bear from Starsky and Hutch, strutting and in a tight afro, a black leather jacket and bell-bottomed blue jeans. The over-the-top antics - including gyrating twirls from Pompey in sunglasses at night - are interrupted by the upstage arrest of the tank-top wearing Claudio, who is handcuffed by blue-uniformed officers and manhandled as the visibly pregnant Juliet looks on. In melodramatic fashion, Claudio leaps atop the table to rail against "the demigod Authority" before being hauled away.

The exaggerated stylings are more difficult to forgive than the sometimes visible stage crew scurrying along the sides of the stage or upstage, or actors seen preparing for cues to enter from the wings. Rauch gamely continues with 1.3, the Duke at a community center in which friars provide hot soup to the homeless, then segueing pointedly to a nunnery as the diminutive Isabela approaches from the audience while choral music plays. The setting, despite similar furniture and props, is distinct from Angelo's 2.1 government office, the strippers from 1.2 now his prim administrative assistants, a U.S. flag upstage. Angelo wears dark judicial robes, self-important and annoyed with the Jamaican-accented but cartoonish Elbow and the drunken buffoon Pompey. The latter is played like Kramer from Seinfeld, tall and gangly with a shock of wild black hair, lurching about in sudden fits and starts. Pompey flirts with Angelo's court reporter, handing her a business card she tucks into her blouse, only to have it taken away by a stern Escalus. The central 2.2 conflict between Angelo and Isabela is dramatically short-changed by the preceding antics, with Angelo recoiling when he touches her hands, then attempting to conceal his arousal by positioning a book at crotch level. When Isabela exits with Lucio, Rauch's lights focus on Angelo and ominous music plays, but the temptation is diminished in impact.

Rauch separates Angelo's temptation from his proposition to Isabela with a brief 2.3, highlighted by visitors - including Juliet - waiting to see their imprisoned husbands and boyfriends. In glaring prison lights and amid jailhouse sound effects, women sign documents, adjust their makeup, and tend to a child in a stroller before becoming Las Calibri and singing about social justice. After the Duke speaks to Juliet via a Spanish translator, Angelo emerges into a 2.4 spot light in a business suit from the opposite side of the stage, intimidating Stephanie Beatriz's Isabela. Beatriz physically plays the role well, tiny in stature but rigid in her forthrightness, but she is tremulous of voice with little inflection or rhythm. She appears deeply frightened as Angelo kneels in prayer, then crouches beside her before looming threateningly over her. When she sheds tears, he begins to sign Claudio's pardon but stops - "my false outweighs your true" - and exits, leaving Beatriz's Isabela alone onstage amid somber violin notes.

Rauch's cut to 3.1 reveals disturbing similarities in Isabela's discussions with Claudio and then with the Duke, punctuated by prison noise and shadows playing against the white screens behind them. Her brother shifts from outrage - "thou shalt not do it" - while they pray together, to second thoughts: of the seven deadly sins, "it is the least." After Isabela curses Claudio in Spanish, she is comforted by the disguised Duke, who lights her cigarette then takes a drag himself in a foreshadowing of his sense of intimacy with her. Heald's Duke becomes excited with his plot to entrap Angelo, although Isabela is obviously uncertain, and when she touches his hand, the Duke pointedly shows the same surprised arousal as Angelo.

The second act begins 3.2 with more broad comedy, seeming out of place after the hard drama of the scenes concluding act one. Elbow chokes Pompey with his billy club before hiding it behind his back and smiling broadly - "bless you Friar" - and after an affected street jive interplay with Pompey, Lucio swigs liquor from a bottle in a paper sack and wages verbal battle with the supposed Friar. The characters are too much caricature to be entertaining, although Rauch mitigates with revealing action upstage between the screens: first Pompey is searched by prison guards then Mistress Done is humiliated, driven to her knees before being exposed in a strip search to be a man - "away with ... her" - and she exits with her hand over her mouth in horror. Rauch's 4.1 is the production's finest scene, presented with welcome subtlety and quiet poignancy. Angelo, wearing a white tuxedo with a red rose in his lapel, is deceived in the bed trick, crooning like a nightclub singer, joined in an unwitting duet by Mariana, his former fiancé.

The 4.2 and 4.3 scenes revert to cartoonish humor, however, with the creepy Abhorson - long-haired and ghoulish in black gloves and sunglasses - spit-shining his beloved electric chair as the Armory's disco ball spins and shoots fractured bolts of light. He uses a bullhorn from stage left to instruct Pompey in death sentences, and an executed man's head is returned to the stage in a Styrofoam cooler while Claudio can be seen pondering a Bible upstage.

Shakespeare's long and difficult single-scene Act V is in this production a rushed and hard-to-follow wrap-up, Heald's returned Duke is frantic, shaking hands with audience members to celebratory music from Las Calibri. He leads a clap-along and dances wildly onstage before stopping at a governmental podium. Now miked, he urges applause for Angelo, gestures for the house lights to be raised for the complaint from Isabela, and checks his watch - "be brief" - impatiently. With uniformed police in the audience wielding clubs, Lucio frequently interjects from a seat offstage right, and the Duke orchestrates the contrived conclusion with an increasingly manic intensity: he barks orders at his Provost, who scurries and runs in place like a keystone kop, and his star witness friar reads woodenly from a prepared script.

Angelo endures with dignity, well-dressed and seated cross-legged at center stage, then erupts - "I did but smile 'til now" - before his crimes are. Angelo falls to his knees then rises to meet Mariana, and by the final moments he is murmuring lovingly to her and holding her hands. Lucio, who had hushed audience members around him when warned to silence by the Duke, comically tries to escape by sliding backward down the steps in front of the stage, but he too is reunited with a former love, ushered in by Mistress Overdone. Heald's Duke resumes his overtures to Isabela - "your Friar now your Prince" - and once Claudio is revealed to be alive: "he is my brother too." Beatriz's Isabela appears indecisive, then walks toward th expectant Duke, but pauses and turns at the podium, eyes shifting one way then the other, leaning into the microphone and inhaling as if to speak as Rauch concludes in a sudden blackout.

The abrupt ending of Rauch's production of Measure For Measure - what is Isabela going to say to the public? - is a clever touch in a social drama that brims with ideas, but is hobbled with makeshift production values and an excess of silly humor.