Summary

A sparsely staged history opens with a telescoping wide-angle view of the to-be-abdicated throne far upstage, but the drama unfolds dryly with basic blocking, feeling at times like a staged reading. A slew of effective if obvious sound effects enhance a solid portrayal of Richard, pouting like a spoiled teenager and unconfident in the affairs of state. Shamed as landlord of England, he is shorn of hair and stripped nearly naked as he makes his personal revelations and finally rises as a self-aware man. Three of his toady followers double intriguingly as his eventual assassins, but the best performances come from Seattle Shakespeare Company's more mature actors, especially the portrayals of an outraged Gaunt and a noble but conflicted York. Few comic moments - most notably the hurling of multiple gages in huffing-and-puffing displays of righteousness - enliven this earnest if too-often stiff historical tragedy.

Design

Directed by Rosa Joshi. Scenic design by Carol Wolfe Clay. Costume design by Jocelyne Fowler. Lighting design by Geoff Korf. Sound design by Dominic CodyKramers.

Cast

David Brown King (Aumerle), Mike Dooly (Mowbray/Abbott), David Foubert (Bolingbroke), Reginald Andre Jackson (Northumberland), Peter A. Jacobs (York), Brenda Joyner (Queen), Robert Keene (Scroop), Dan Kremer (Gaunt/Gardener/Groom), Martyn G. Krouse (Carlisle, Lord Marshal), Jason Marr (Bagot), Victor Matlock (Green, Murderer), Alex Matthews (Willoughby), George Mount (King Richard), Jay Myers (Bushy, Murderer), Brandon J. Simmons (Ross), Kate Wisniewski (Duchess of Gloucester/Duchess of York).

Analysis

Seattle Shakespeare Company's Richard II begins with a telescoping view of the upstage throne as if through a wide-angle lens, the throne empty but ominously lit by claustrophobically low-hung side lights. Director Rosa Joshi dresses the stage sparsely, focusing instead on the characters mostly downstage center, the stage hardwood flooring, the side walls draped in black curtains. In brightening light and drum roll, the throne is wheeled downstage and George Mount's self-conscious Richard sits at center stage wrapped in a creamy white robe like a toddler in a snuggie, a ring on every finger, cuddling his scepter. He is flanked by five courtiers on each side and hears the 1.1 arguments between Bolingbroke and Mowbray, but the declamatory shouts feel stiff and there is little room to move, like a simple staged reading. Little tension imbues the scene, which continues 1.3, the most dramatic moment coming when Mount's Richard merely leans forward from the throne. The King inspires interest, however, with his prissy expression and ultra-superior demeanor, forced to be serious but bored by the whole proceeding, and he squirms in the throne like a sugar-addled child.

The conflict between Mowbray and Bolingbroke remains central, but is fractured - the two scenes split by a blackout then a dramatic glimpse into the sickly old Gaunt in his shredded shades of brown. Richard elicits nervous laughter when he petulantly throws down his gage to halt the quarrel - "our doctors say this is no month to bleed" - and when he returns amid fanfare he seems to notice the crowd applause for Bolingbroke is stronger than it was for even him. Other moments are just as subtle - Bolingbroke reluctantly kissing the King's ring but dropping to a knee in humility before Gaunt - but for the most part the action unfolds at a steady if plodding pace. Mowbray alters between angry bluster and showy superiority - "truth has a quiet breast" - before being banished 1.3, and the steady confidence of Gaunt ("there is no virtue like necessity") in 1.4 feels as if it will be truly missed. The scene ends with a swarm of caterpillars and hangers-on badly practicing chanting and laughing too loudly.

Joshi culls the production's best performances from the more mature performers in the company, most notably Dan Kremer and his expertly-spoken Gaunt, indignant but never sputtering, subtle but never insignificant. The fiery "this England" speech 2.1 is the highlight of the production's first half, and the condemnation as "landlord of England, not King" leaves Mount's Richard sputtering, his lower lip trembling like a spanked toddler. When Kremer's Gaunt raises an accusatory finger but collapses, the King's relief is apparent - "so much for that" - as he turns his attention to his own self-serving whims: "now to these Irish wars." In an equally small but effective role, Peter A. Jacobs' conflicted York is admirably loyal to a King he does not respect, rebuking the strutting Bolingbroke 2.3 with a disgusted, "grace me no grace!" Kremer returns 3.4, doubling as the Gardener for the troubled queen, carrying a tiny scythe to rid her garden of pests like she should have done in Richard's court, then again 5.5 as the Groom of the deposed King, breaking the royal heart with his description of a favorite horse and its pride in bearing the new King in public.

A wide array of incidental sound effects enhance the production, a few too loud and obvious, as if designed for a radio performance - fanfares, an audience cheering, crowd applause - but for the most part evocative, from choral chanting and drum rolls, to galloping horses, birds around the garden, and high winds, and at times exceptional, like offstage beheading executions, the seaside noises at the return from Ireland, water drips in the dank dungeon, and softly tolling bells after murder of the King. But Shakespeare's play is a star turn, and Mount's tragically insipid Richard remains at the center of the story. He kneels and claws the ground of his homeland 3.2, registering an uncomprehending shock at the news of subjects abandoning the anointed King, sitting then removing his crown to signal intermission with a characteristically peevish outburst: "discharge my followers!" During 3.4 he seethes, elevated upstage in a spot light, a bit intimidated by the thundering Northumberland at stage right, but he acquiesces, despite his position of divine right: "I must not say no."

Before Mount's closing Act 5 dramatics, Joshi provides a few rare moments of humor 4.1, first with the newly crowned Bolingbroke bemused by the sputtering proclamations of loyalty and the litany of challenges, with gage after gage - I counted seven - hurled to the stage in melodramatic rage. Moments later, Mount's agonized Richard relinquishes the crown - "ay, no; no; ay" - despite his misgivings, offering Bolingbroke the crown, then taking it back, then giving it away but knocking it from Bolingbroke's grasp, finally chasing it like a child after a ball before kicking it away from himself.

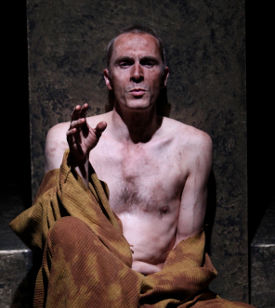

Mount's finest moments come in 5.5 - after Bagot doubles as the murderer Piers Exton, answering the new King's 5.3 call of "do I have no friend?" - his long brownish hair now dramatically shorn, standing manacled and all but naked in the dripping darkness of a dungeon. Mount's Richard seems self-realized, finally appreciating what is around him - "music, do I hear?" - and admitting his folly ("I wasted time, and now doth time waste me") before rising to wage an unwinnable fight against armed murderers. During 5.6, to the ominous sound of tolling bells, Joshi's production concludes with the striking image of Bagot dragging the slain former King on a bloody blanket to be paraded before the new King. Bolingbroke, now Henry IV, condemns the act, setting forth some of the themes that will follow in the later plays of the tetralogy, and concluding the Seattle Shakespeare Company's too-straight-forward but nonetheless effective historical drama.