Summary

First-ever production of a Shakespeare play by a renowned Chicago company is a racially cast extravaganza of special effects. A flower-child college professor Prospero oversees the storm that brings his enemies under his influence, but he is underplayed, with themes refocused onto the servitude of Caliban and the magical servant Ariel. Garish color, crude visual humor, and an explosion of big-budget theatricality overwhelm the production, which concludes with Ariel's stirring race to freedom.

Design

Directed by Tina Landau. Set by Takeshi Kata. Costumes by James Schuette. Lights by Jane Cox. Original music and sound by Josh Schmidt. Projections by Stephen Mazurek. Aerial choreography by Sylvia Hernandez-DiStasi.

Cast

Frank Galati (Prospero), Alana Arenas (Miranda), Jon Michael Hill (Ariel), K. Todd Freeman (Caliban), Stephen Louis Grush (Ferdinand), Craig Spidle (Alonso), Mike Nussbaum (Gonzalo), Alan Wilder (Sebastian), James Vincent Meredith (Antonio), Tim Hopper (Trinculo), Yasen Peyankov (Stephano).

Analysis

Steppenwolf Theatre - founded in suburban Chicago in 1976 - presents its first Shakespearean production with a racially cast and extravagantly produced The Tempest. The high-priced theatrics, overtly showy and beyond overkill, blunt the dramatic potency of Prospero and his magical vengeance and humane forgiveness, and director Tina Landau deliberately shifts the thematic focus from Prospero to his two island natives, Ariel and Caliban.

Landau's production begins with a dramatically sudden blackout and deafening thunder crash. Frantic sailors emerge from stage traps and climb down from ropes suspended both over the stage and from mid-audience, twisting and flailing in mid-air as peals of thunder like explosions continue to crash. Strobe-like lightning imbues the cacophony with a sea-storm desperation, and a ship's mast falls to a crooked angle across the stage. The pandemonium halts for a freeze-framed moment as Gonzalo - in this performance portrayed by an understudy male actor rather than the original cast's woman - speaks from a wheelchair amid sailors with flashlights and lanterns. Landau's barebones stage, stripped down to brick and cinderblock and bare planks, features billowing upstage sails, coils of heavy rope, and a metal ramp that spans the width of the stage, rising to a platform upstage left.

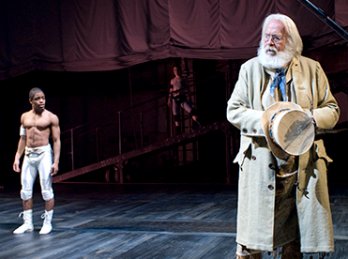

The intensely raucous beginning concludes in sudden silence, with Frank Galati's Prospero seated calmly downstage center. Galati's gentle Prospero, in long white hair and beard, wire-rimmed spectacles and strapped sandals, resembles a hippie college professor or a kindly Santa Claus, and his softly spoken speech furthers the image. With video images of rolling waves on a quiet beach projected on the upstage sails, Galati's pale-skinned Prospero, his robes tattered and rag-like, addresses the audience and then Miranda in a long sequence with a quiet gentility that contrasts with the commotion of the opening scene. Miranda, played by a young African-American actress barefoot in a white dress, reveals naïveté - "sir, are not you my father" she asks, oblivious of race or color of skin - as well as strong intelligence. With both Prospero's daughter and brother Antonio dark-skinned as well as both island denizens Ariel and Caliban, Landau provides insights into both white domination and black yearning for freedom.

Ariel (and to a lesser extent, Caliban) overshadow Prospero in Landau's conception of The Tempest. Jon Michael Hill's Ariel - an exuberantly physical young man, shirtless in silver spandex football pants and knee pads - dominates the production from his initial appearance, "flying" in from the rear of the audience on a zip line cutting diagonally high above the orchestra seats. He leaps from a stage-right box down to the stage, followed by his three spirits, an equally agile crew - two young man and a woman - wearing gray and black workout gear and pads. Hill's chin-bearded Ariel resembles a television sports gladiator, well-muscled and athletic, and he is revealed to be the true magical power on the island. A restless black man yearning for his freedom, he cavorts in carnival-like acrobatics with his fellow spirits, and he wears a head-set microphone to sing for Ferdinand, leading him to safety on the beach, and he bellows in amplified booms to frighten Stephano and Trinculo. Strangely, Ariel later uses a MacIntosh laptop personal computer to manipulate sound effects and images to awe and confuse the castaways. Hill's Ariel can soften the playing of music with just a wave of his hand, and he conjures the raising of a purple-and-yellow flower from the "sand" onstage, but he remains beholden to Prospero. Prospero's mere mention of Ariel's tormentor, the witch Sycorax, causes Hill's Ariel to spasm within an electronic hum as if within the throes of an epileptic seizure.

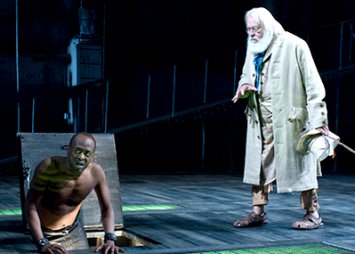

Landau presents the earthly Caliban as the ethereal Ariel's opposite, and the beast emerges from the stage-fog murk of a trap, shackled in chains, wearing rags, and scarred across his chest and abdomen. Like Ariel, Caliban is a young black man desperate to be set free by the mellow but prevailing Prospero, and he defies Prospero - "I know how to curse" - giving the sorcerer "the finger," and quickly becoming drunk and belching, choosing to ally himself with the degenerate Stephano. The comical scenes with Stephano and Trinculo are disconcertingly vulgar, an over-the-top counterpoint to Ariel's basic benevolence. Whereas Ariel gently seats the kindly old Gonzalo in his wheelchair and puts a blanket over the sickly man's legs, Calilban wrestles with Trinculo in an inverted and overtly sexual position - "Is this a man or a fish?" Stephano wonders - and he scrabbles on the stage like an animal after Stephano and his jug of rum. Stephano, wearing a floppy vinyl rain hat and raincoat, squats to defecate in the sand, and he feeds Caliban from a jug of liquor suspended at his crotch as if he is being fellated. He rubs and caresses Caliban's bald head as the creature drinks for disturbingly long moments until both Stephano and the audience become uncomfortable. Trinculo, wearing tuxedo ruffles, a red bow tie, and wing-tipped shoes, comically sports long shorts and stylish sunglasses as well. His farcical fisticuffs with Caliban are observed by Ariel and the spirits, posed upstage in hanging carnival-like positions along heavy mast ropes, but when Caliban longingly speaks and then sings of his freedom, Ariel is moved and comes forward, mouthing the word himself.

King Alonso and his court, portrayed in garish violet and hot pink formal suits - some with top hats, key fobs, tails, or vests - present the Old World elite, awash and out of their element on Prospero's island. The incongruent splash of neon color is jarring, and the production takes a hyper-dramatic albeit audience-pleasing turn. Landau, emboldened by an enormous Steppenwolf budget and the capability for extravagant theatricality, veers even further from the diminished theme of Prospero's transformation into a forgiving gentleman as well as from the African-American island denizens' quest for freedom, and the production becomes an oddly Alice in Wonderland-like, LSD-trippy spectacle. Lighter and more subtle moments - a shirtless and heavily tattooed Ferdinand has his work-pile of lumber sneakily increased by Ariel's spirits; Stephano bows and removes his hat and inadvertently his ghastly black toupee as well - give way to gaudy and absurd imagery: during the magical banquet, Ariel appears upstage like a gigantic bumblebee, his arms splayed like sharp, Edward-Scissorhands-like wings and his lower body a giant metallic bee thorax, his voice amplified and booming to terrify the King and his men; Ariel conjures dozens of three-foot colorful poppies that descend from the fly like a flower-shower amid thumping club music and strutting hip-hop dance routines from the spirits; and the wardrobe for Stephano and Trinculo features feminine dresses, gowns, stoles, wraps, and minks that they don and display in fashion-show runway struts - pouting and prancing upstage to twirl and march back upstage, hands on hips - before they are pursued offstage by the spirits wearing ghastly hyena heads with devil's horns. And when the goddess Juno is summoned by Ariel, she appears as a fifteen-foot-tall apparition in a flowing white chiffon dress, while modern techno music blares, Ariel raps, and the spirits gyrate as if at a nightclub. Tellingly, Galati's Prospero must halt the dancing and music, and he brings the production thankfully back into focus: "I had forgot that foul conspiracy!"

Landau's psychedelic production, in its concluding moments, achieves a welcome sense of quietly dramatic resolution after the preceding hour of garish theatricality. Galati's Prospero, less a master magician than a soft-spoken intellectual - one Chicago reviewer likened him to a technology CEO overwhelmed by and unaccustomed to out-of-control modern inventions - moves to a circle of light downstage center: "now my charms are all o'erthrown." He breaks his wand-twig in half and drops his tiny book of magic to the stage, out of the circle of light, as Ferdinand and Miranda appear arm-in-arm in one of the box seats above stage right. As Ariel croons "where the bee sucks" - a vague reference to his earlier appearance as a gargantuan bumblebee - in anticipation of his promised freedom, Prospero individually forgives his governors, even his usurping brother, and again dons the oddball bright pink clothing of a government official. Caliban accepts his freedom, and after Antonio stalks offstage, Hill's ebullient Ariel steps to center stage. With a beaming smile, Ariel raises his arms and leaps from the stage, racing through the audience and out of the theater in a moving final moment far more evocative than any of the hallucinogenic and bombastic special effects that preceded it.